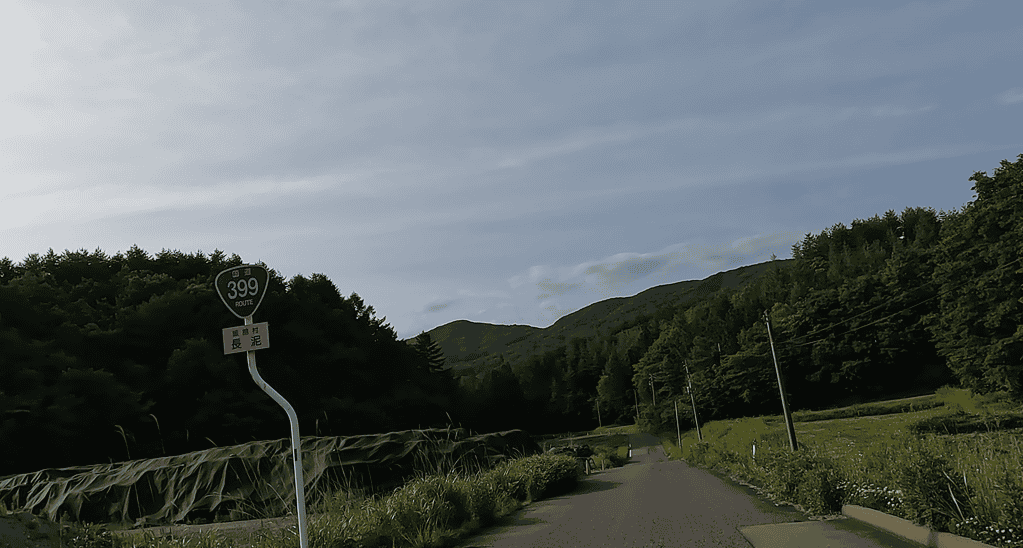

Route 399

Or, as some call it…

“Route 399 – The Road from Hell”

I first heard about its infamous reputation from the book “Kokudo Daikōhyakka” by Shigeo Kakutori (published by Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha).

To most people, the term “national highway” brings to mind well-maintained roads funded by the government—smooth, wide, and reliable.

And sure, many highways fit that description, serving as major arteries cutting through towns and connecting regions.

But not this one.

Some so-called national highways are narrower and rougher than local roads—looking more like abandoned trails than proper thoroughfares.

Some sections are so tight that cars can’t even pass each other, with crumbling shoulders and stretches of unpaved gravel.

It’s enough to make you wonder whether “national highway” is some kind of cruel joke.

In the book, roads like these are collectively referred to as “Kokudo”—the Brutal Roads.

Sure, they’re far from ideal for work or logistics, but if you’re in it for the thrill of exploration, they’ve got an irresistible charm.

Among the Brutal Roads featured in the book, there are a few in the Tohoku region.

The one that looked closest to home was Route 399.

Route 399 starts from Iwaki City, Fukushima Prefecture, and stretches about 170 km to its endpoint in Nanyo City, Yamagata Prefecture.

Most of it slices right through the rugged Abukuma Mountains of Fukushima.

It runs northwest from Iwaki, passing through Kawauchi Village, Tamura City, Katsurao Village, Namie Town, Iitate Village, Date City, and Fukushima City.

It briefly dips into Shichikashuku Town in Miyagi Prefecture before heading back into Fukushima City and then crossing into Takahata Town, finally ending in Nanyo City, Yamagata.

At around 170 km, it sounds like a fairly short trip for a day tour.

But don’t be fooled—this is all winding mountain roads, so speed isn’t exactly on the menu.

In other words, it takes way longer than you’d think.

And just to crank up the difficulty another notch, there’s the approach to the starting point (or endpoint).

It’d be nice if it were close to home, but unfortunately, both ends are a long haul away this time.での

- The Journey from Home to Iwaki

- Route 399 – Starting Point: Iwaki City

- Kawauchi Village – Tamura City

- Katsurao-Village, Namie-Town, Iidate-Village

- Date-City, Fukushima-City (Iizaka Onsen resort)

- Hatomine Pass

- Ryugatake – Climbing Adventure

- Takahata-Town(Shrine of the Dog / Shrine of the Cat)

- Route 399 – Endpoint: Nanyo City

- Appendix

The Journey from Home to Iwaki

The Usual Pre-Departure Photo

Here we go—the classic pre-ride shot.

First things first, I’ve got to get to the starting point in Iwaki City.

The distance from home? A whopping 160 km…!

That’s practically the same distance as the entire Route 399 itself! (Yeah, hilarious.)

But there’s no point in complaining, so I hit the road, hugging the coastline as I make my way to Iwaki.

Personally, I highly recommend taking the route that connects Yuriage in Natori to Namie Town.

The GPS will try to steer you onto National Route 6 or the expressway, but the locals know better—

the Hamakaido or Prefectural Route 38 (Soma-Watari Line) is the way to go.

Fewer traffic lights, better views, and some cool stops along the way.

One of my favorite spots is Hama-no-Eki Matsukawaura in Soma City, right where the road skirts Matsukawaura Lagoon.

It’s got loads of local goodies—fresh veggies from nearby farms and seafood caught just off the coast—all at really reasonable prices.

Perfect place to stretch your legs and pick up some snacks for the road.

They’ve got some seriously plump and flavorful live clams, and the local specialty—hokkigai (surf clams).(And yes, I actually tried them—totally worth it.)

They also sell impressive, fresh veggies at bargain prices, and outside, you’ll find some tasty grilled seafood stalls—like a seaside barbecue vibe.

On weekends, you’ll often spot riders cruising around here too, so planning a ride through the Soma area isn’t a bad idea at all.

Heading south over the Matsukawaura Bridge, you’re greeted with a view that’s uniquely Matsukawaura.

(Just a heads-up—the photo was taken a few weeks back.)

This straight stretch of road feels amazing to ride.

You could blast through it in one go, but honestly, taking a break at the lookout point to soak in the scenery is worth it too.

If you find yourself in Minamisoma, there’s one spot you definitely shouldn’t miss—Kashi Kobo Watanabe.

Their cakes are amazing, but the real star this time of year is their seasonal soft serve.

Highly recommended!

Passing through Minamisoma City, I made it to Namie Town just in time for lunch.

Most tourists around here tend to stop by the roadside station, but this time I decided to check out a recently opened burger joint called Aspiration.

This burger’s got some serious volume.

Apparently, the patty uses Fukushima beef, which definitely adds to the appeal.

Tomato, lettuce, and other toppings are optional, so you can build it just the way you like.

And the potatoes? Not your usual fries—they’re hash browns.

After leaving Namie Town and entering Futaba Town, you’re practically at the doorstep of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.

You can’t see the whole facility, but it’s obvious when you’re there—you just know.

These days, traffic restrictions have loosened up quite a bit, and that day I even saw a foreign tourist on a bicycle coming from Iwaki, pedaling down Route 6.

I could just keep heading south on Route 6 to reach Iwaki, but where’s the fun in that?

Main roads are boring, so I took Prefectural Route 35 instead, which runs parallel.

As I rode through the mountains of Namie, Futaba, and Okuma Towns, I saw small alleys still blocked off with barricades.

The scars of the disaster are still deep and unhealed.

This is a photo from when I rode through Namie Town back in April.

As you can see, there are still some areas in the outskirts where traffic restrictions are in place.

Route 399 – Starting Point: Iwaki City

I arrived in Iwaki a little after 2 PM.

Yeah, pretty late for the start of a touring ride, but it is what it is.

This seems to be the starting point… I guess?

Anyway, I spotted a Route 399 sign, so I snapped a quick commemorative photo.

I’m pretty sure I’m on Route 399, but since it overlaps with Route 6 for a while, it doesn’t really feel like it.

The road loops around to the north exit of Iwaki Station, weaving through residential areas as I head north.Before long, the scenery opens up to sprawling fields, and in less than 30 minutes, I’m riding through a forested road.

Up ahead, my partner is riding smoothly.

Weekends can be a bit of a hassle with Sunday drivers clogging up the road, but today it’s surprisingly pleasant.

By the way, there’s a tunnel called Jumonji Tunnel right around the border between Iwaki City and Kawauchi Village.

It’s brand new—opened in 2022—but before that, the route was a narrow, winding road snaking through the hills.

When the “Kokudo Daikohyakuka” book was published, that old winding road was still considered part of Route 399.

Technically, the new tunnel diverts from the original Route 399, but if you’re looking for a wilder, more rustic ride, the old road is definitely the way to go.

Kawauchi Village – Tamura City

I took a break at YO-TASHI, right after entering Kawauchi Village.

A few riders came and went while I was there, but honestly, it felt pretty quiet for a weekend.

After leaving Kawauchi and crossing into Tamura City, the scenery stayed just as peaceful—wide, open fields stretching out on either side.

There’s something really nice about these pastoral landscapes.

Just cruising through without a care in the world—it’s the kind of vibe that makes you forget about the hustle and bustle.

Katsurao-Village, Namie-Town, Iidate-Village

From Katsurao Village to the western part of Namie Town, and then on to Iitate Village, the atmosphere changes dramatically.

Not too long ago, these roads were completely blocked off with barricades, making them impassable.

And before that, the entire area was sealed off, leaving nothing but haunting, desolate views from the Joban Expressway.

On May 1, 2023, along with several other towns and villages, the evacuation orders were lifted, finally allowing unrestricted access.

But that’s just on paper.

Riding through areas once designated as difficult-to-return zones, it becomes painfully clear—there’s no sign of life.

Not a soul to be seen.

Just quiet roads cutting through empty landscapes, reminding you that some scars take a long time to heal.

The phone signal’s completely gone, and there are hardly any cars passing by.

Just thinking about having a breakdown here sends a chill down my spine.

As I was descending the mountain road in Iitate Village, I spotted something lying in the road up ahead.

A plump little creature—was it a tanuki? A weasel? Maybe a marten?

Usually, animals like this get spooked by bikes or cars and bolt like their life depends on it.

But this one just lazily shuffled off into the grass, totally unbothered.

Guess it’s not used to seeing people around here—no sense of caution at all.

Seeing scenes like this and keeping them in mind feels almost like a duty for us modern folks.

A reminder that it’s not over yet—far from it.

Not just on this road, but anytime I’m riding along a lonely, remote mountain pass, knowing there’s a roadside station nearby gives me a real sense of relief.

Date-City, Fukushima-City (Iizaka Onsen resort)

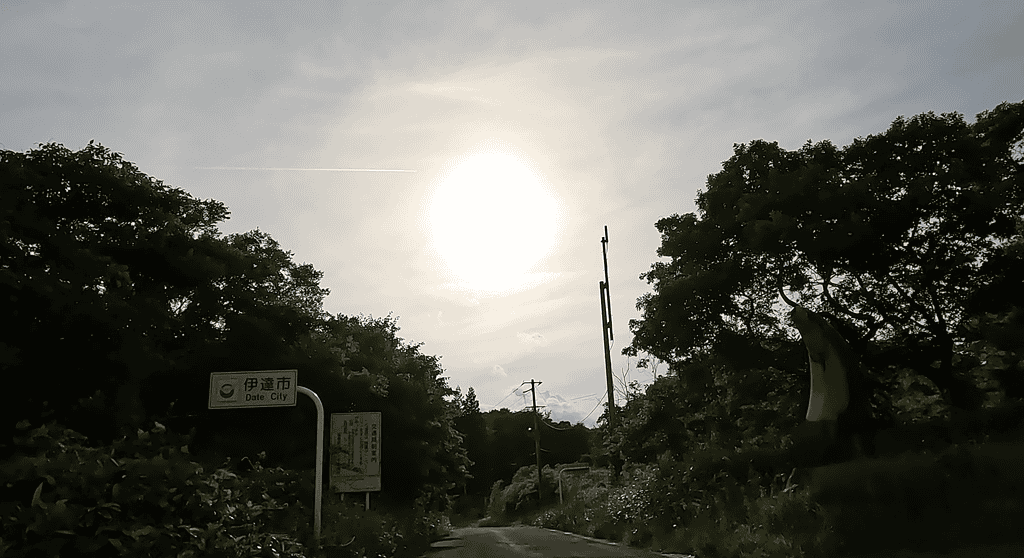

By the time I entered Date City, the sun was already dipping low in the sky.

The scenery gradually got livelier as I rode through the bustling streets of Date, and before I knew it, I was in Fukushima City.

I reached Iizaka Onsen around 6 PM.

Usually, touring means camping out in a tent, but my partner was having none of that.

So, it was a night at Iizaka Onsen instead.

The place we stayed this time was Iseya.

It’s a bit tucked away from the center of Iizaka Onsen, but for riders, it’s a gem—they’ve got a covered parking area just for bikes.

The staff were all wearing Moty’s T-shirts, so I’m guessing the owner is a bit of a gearhead too.

The building itself is a little on the older side, but it’s easy to imagine how it must have been bustling with tourists back in the heyday of the Showa era.

There’s a certain nostalgic charm to the place that makes it feel welcoming.

It only takes a little over 10 minutes to get to Iizaka Onsen Station, the gateway to Iizaka Onsen, so it’s not inconvenient at all.

Actually, when a hotel is too convenient, it makes you lazy—like, “Ah, let’s just stick around here”—and kills your sense of adventure.

So in that sense, this place was just right.

Iizaka Onsen isn’t just from the Edo period—it’s even tied to the legendary Yamato Takeru, who supposedly healed his wounds here.

Back in the 1970s, it drew around 1.77 million visitors per year.

Even now, you can still see the remnants of that golden age—abandoned hotels that must have been pretty grand in their prime, and old apartment buildings that probably housed hotel staff. You can almost picture what it must have been like back then.

The center of Iizaka Onsen is crisscrossed with one-way streets, so you’ve got to be careful, especially on Prefectural Route 319 in front of Hotel Juraku.

It looks like it’s one-way from the station, and I saw a patrol car stopping cars coming from the opposite direction.

The problem is, there’s no visible sign from the intersection side, so if you got pulled over for that, it’d be pretty frustrating.

After tossing my stuff in the room, I took a stroll around the onsen town.

True to its long history, many of the buildings carry a distinct sense of the passage of time.

Iizaka Onsen isn’t just about historically significant buildings with academic or cultural value—it’s also got this nostalgic Showa-era vibe that you can’t help but appreciate.

As I wandered around town, I started feeling hungry.

It’s not like I just stumbled off a random station, but let’s be honest—grabbing a meal while traveling is always a bit of a gamble.

One wrong choice, and the whole trip feels ruined.

So… what should I go for?

This time, I decided to go with Gyoza no Terui.

They’re known as the originators of enban gyoza—a style where the dumplings are arranged in a perfect circle.

It’s a popular spot, and sure enough, the line was massive.

I wrote my name down and ended up waiting more than 30 minutes to get in.

Of course, I had to order the gyoza, but for some reason, this place also pushes horse meat.

Horse sashimi isn’t that uncommon, but they’ve got some unique stuff here—like “uma awabi” (literally “horse abalone”), which is actually the pulmonary artery of a horse.

And surprisingly, they serve horse liver too.

Beef liver has been completely banned for a while now, but apparently, horse liver is still on the menu.

Can’t remember the last time I had raw liver… it’s been years.

So, I went ahead and ordered the horse liver.

Honestly, if someone told me it was beef liver, I probably wouldn’t have noticed—it’s got a milder taste, not as bold as beef.

To be honest, I wasn’t feeling great that day, so I figured a little liver might help revive me.

And here it is—the enban gyoza.

A single plate comes with 22 pieces.

Normally, when you order gyoza at a typical ramen joint or a local Chinese place, it’s one or two plates—maybe around 10 pieces in total.

So 22 should feel like a lot… but somehow, I polished off the whole plate without even breaking a sweat.

To top it off, I went ahead and ordered some ramen too (yeah, couldn’t resist).

The ramen had that classic, no-frills flavor—simple and delicious.

They also offer a half plate of gyoza, so I’d definitely recommend getting the ramen and gyoza as a set.

With a full stomach, I decided to walk off the meal and resume exploring the town.

By the time I left the shop, the sun had already set.

The scenery I had just seen earlier looked completely different now that the sun had set.

It’s funny how the same place can feel almost like a whole new world just because the night has fallen.

I’d heard about this onsen town for ages—it’s just over the border in Fukushima, after all.

But maybe because it’s so close, I never really thought to visit.

This time, it was just a quick stop on my touring route, but next time, I’d like to take my time and really explore.

The next morning, I discovered a place called Sobahiro that opens as early as 7 AM.

It’s run by Hirosuke Ryokan, but it’s not just for guests—anyone can drop by for a bite.

All this for just around 500 yen.Now that’s what I call a bargain.

After finishing breakfast, I left the inn and got back on the road to continue the tour…

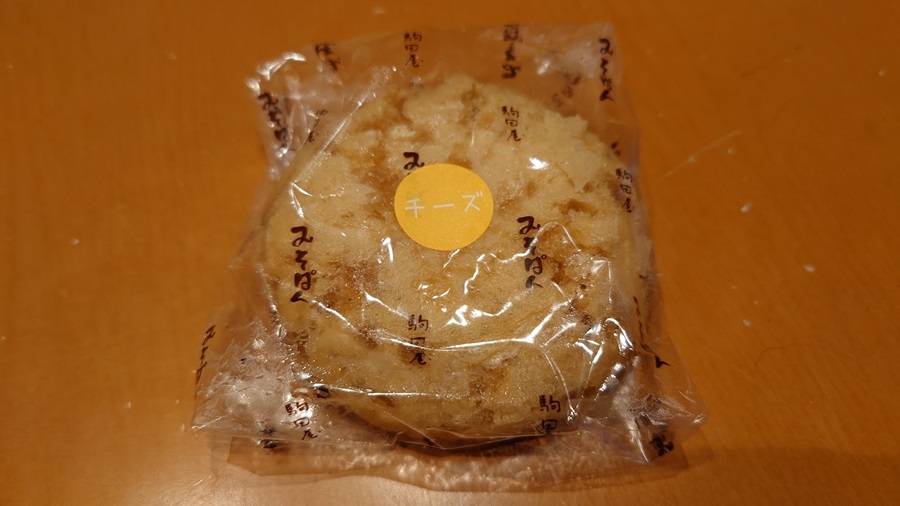

But before that, I made a quick detour to Komadaya Honpo in Fukushima City, which I couldn’t visit yesterday due to running out of time.

Unfortunately, I forgot to set up the camera, so no footage of that, but on the way toward Fukushima Station, I ended up riding parallel to a local train on the line connecting Iizaka Onsen and Fukushima Station.

The train and the station both have this great retro vibe, so I’ll include a photo I took previously at Fukushima Station.

Here it is—Komadaya Honpo.

It’s just a few minutes by car from Fukushima Station.

I picked up their specialty—miso bread.

Lately, they’ve even started offering cheese-filled miso bread, and I got to try one fresh out of the oven.

Absolutely delicious!

Hatomine Pass

With souvenirs safely packed away, it was time to get back on the Kokudo Touring.

The road follows the Surikamigawa River as it flows through Iizaka Onsen—a surprisingly smooth and spacious ride.

Before long, I came across the Surikamigawa Dam and its reservoir, Moniwako Lake.

At Moniwa Hirose Park, there’s even a free campsite.

And right next to it, there’s an onsen facility called Moniwa no Yu.

A free campsite with a hot spring just a stone’s throw away?

That’s about as good as it gets.

However, there aren’t any grocery stores nearby, so it’s best to stock up on supplies beforehand.

If you’re coming from the Iizaka Onsen side, grab what you need at a supermarket around there.

If you’re approaching from the Yamagata side, make sure to pick up your food in Takahata Town.

Once you pass this point, it’s nothing but winding roads ahead.

Some of the corners have pretty tight radii, but the road itself isn’t overly narrow, so it’s generally a comfortable ride.

That said, you do need to watch out for oncoming cars—especially drivers who aren’t used to mountain passes and end up drifting over the center line.

I also noticed quite a few bikes taking corners a bit too wide.

Acting like a pro and ignoring safety margins is a quick way to end up regretting it.

Stay sharp and ride smart.

Hatobone Pass, located on the border between Fukushima Prefecture and Yamagata Prefecture.

From here on, it’s not just the bike taking on the Kokudo challenge—it’s me versus the road.

Ryugatake – Climbing Adventure

I got roped into this climb by my partner, who’s an avid hiker…

Or rather, it just so happened that there was a mountain along our touring route, so the climb somehow made it onto the schedule.

I’ve tagged along on a few hikes before, and it’s always the same—completely wiped out by the end.

Sometimes I even end up with some serious knee pain.

It’s like a guaranteed endurance test every time.

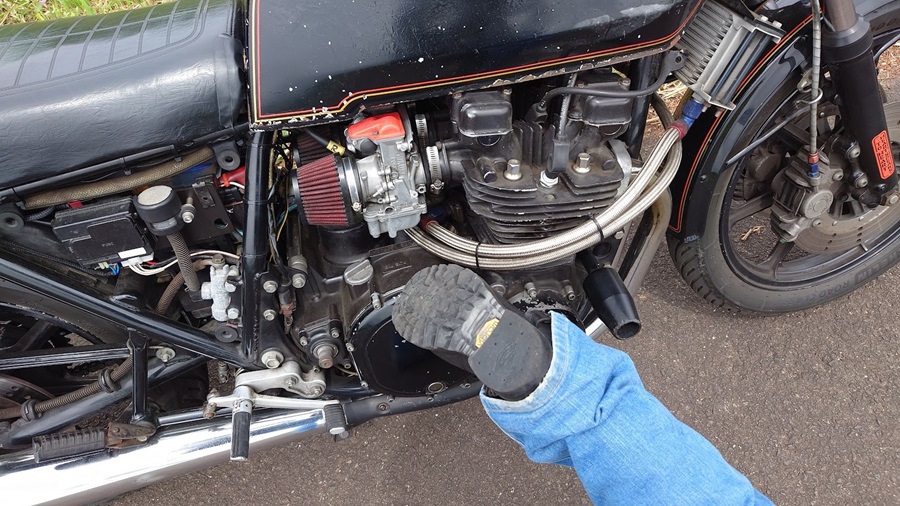

These boots? I picked them up about 25 years ago at some thrift shop in Ueno.

The leather’s cracked and worn, but I had them resoled with Vibram soles, and they made a spectacular comeback.

The real question is—can I actually hike in these?

Can you see the bike parked down there?

We’ve only been climbing the trail for about 10 minutes, and already we’ve got this view.

Our real ascent starts from here.

If the whole trail was this flat, hiking would be a breeze.

Feels more like trekking than actual climbing.

Every time I look back, the view just keeps getting more and more beautiful…

But at the same time, my heartbeat’s picking up faster and faster.

It’s not so steep that I have to use my hands and feet to climb, but there are sections where branches cover the trail, forcing me to stay hunched over while moving forward.

That part’s a real pain.

Apparently, it only takes about 40 minutes to reach the summit, so the difficulty level is considered “easy.”

Yeah, right… tell that to my legs.

Somehow, I managed to make it to the summit in one piece.

It’s the same with any mountain—once you reach the top and take in that breathtaking view, all the exhaustion just melts away.

But then reality hits—you still have to get back down.

Climbing up just leaves you out of breath, but descending? That’s when your knees take a beating.

If I mess up and get injured here, I’m not making it home.

So, I’ll take it slow and careful on the way down.

I started the hike at 10:40 and made it back to the parking lot around noon, so about 1 hour and 20 minutes in total.

To recharge, I treated myself to the mame daifuku I picked up this morning along with the miso bread.

Nothing like a sweet pick-me-up after a tough climb.

Takahata-Town(Shrine of the Dog / Shrine of the Cat)

Once you pass Hatobone Pass and descend to the foot of Takahata Town, you can pretty much say that the Route 399 journey is coming to an end.

But before heading to the final destination, I took a little detour to a unique spot—

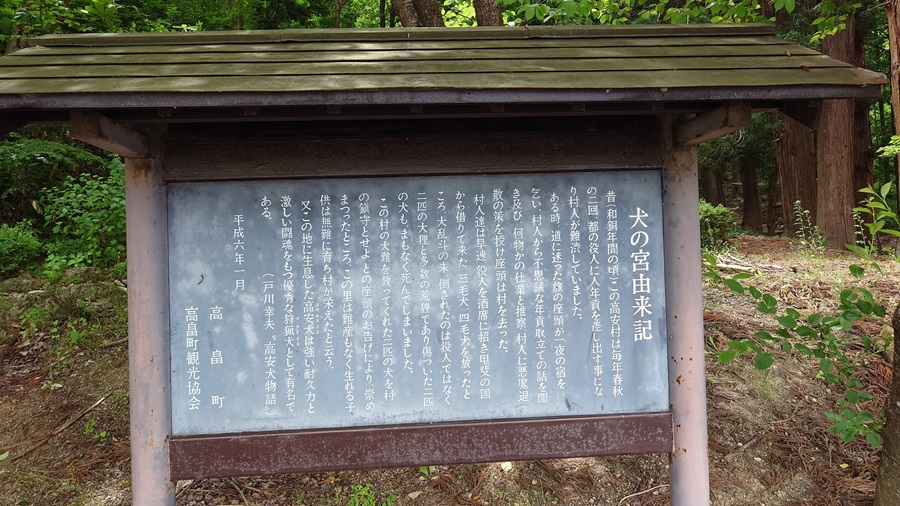

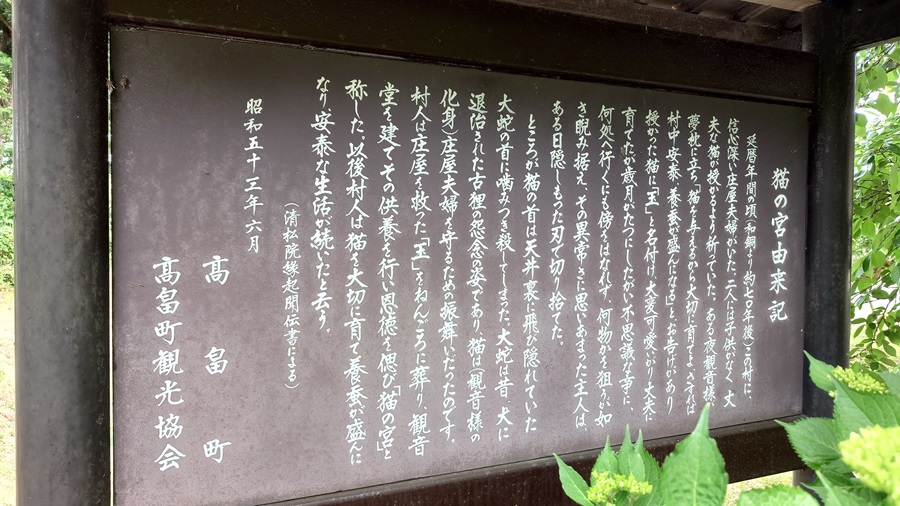

the Shrine of the Dog and the Shrine of the Cat.

Just like the names suggest, these are shrines dedicated to dogs and cats.

For the full story, check out the “Origin Story” sign in the photos.

But in short, it’s a mix of getting tricked by a yokai tanuki, accidentally killing a cat that was actually guarding against snakes…

Honestly, my family roots trace back to this very village.

So if the legend is true, it’s entirely possible that one of my ancestors might have been the idiot who messed up.

If that’s the case, I guess I should say:

“Sorry about my boneheaded ancestor.”

Route 399 – Endpoint: Nanyo City

From Shrine of the Dog,Shrine of the Cat to the endpoint, the route gets a bit tricky to follow.

Once you hit the city center, the road overlaps with other national highways, making it easy to veer off Route 399 without realizing it.

To be honest, the whole “Kokudo” vibe pretty much vanishes as soon as you descend into the city.

But hey, I started from the beginning, so I’ve got to see it through to the end.

At long last, I reached the designated endpoint.

If you don’t count all the little detours and just stick to refueling and short breaks, it’s roughly a 6-hour ride to conquer the whole route.

As time goes on, even roads known as “Kokudo” gradually get paved and expanded, becoming more like any other normal road.

Route 399 now has proper tunnels and improved sections, making it much easier to ride.

Still, here and there, you can spot plenty of scars left by the Great East Japan Earthquake.

But that doesn’t mean we need to get overly serious about it.

Just like the Hamadori region of Fukushima, I think it’s important to actually visit these places firsthand.

Instead of just listening to stories or watching the news, go there, eat something local, and see how it feels.

If your honest reaction is “Man, this must’ve been rough,” that’s totally valid.

Or maybe you’ll be pleasantly surprised and think, “Hey, this place is actually pretty nice.”

What I’m trying to say is, don’t just take my word for it—or anyone else’s, for that matter.

Whether it’s blogs, articles, or media reports, don’t just assume they’re the whole truth.

Whenever possible, go there yourself and see it with your own eyes.

This trip gave me a lot of new perspectives on Fukushima, and it made me want to explore even more routes within the prefecture.

There’s still so much left to discover, and I’m already looking forward to the next ride.

Appendix

I wrapped things up around early afternoon, so on the way back, I decided to go for some local Yamagata specialty—niku soba.

Stopped by Soba-dokoro Mizuki-an in Nanyo City.

The rich, savory flavor really hit the spot—just what my tired body needed.

I was pretty wiped out by that point, but still had about two and a half hours left to get home.

Like I always say—the journey’s not over until I’m back at the starting point and kill the ignition.

This time around, both bikes pulled through like champs—the air-cooled Z and the water-cooled Z, which made its long-distance debut.

The Z1R did start having a bit of trouble with the shifter toward the end, though—probably time for an oil change.